On March 30 and March 31, 2023, our conference “From the 'Workshop of the World' to 'Systemic Rival'? – International Perspectives on Global China” took place in Hamburg. Renowned China experts from politics, academia, business and media analysed the changing narratives on China in different regions of the world and their political implications.

The conference was kicked off by Dr Martin Albers (City of Hamburg) who gave an input on Helmut Schmidt’s view on China and his influence on China narratives in Germany. Here you can read Martin Albers’ introductory remarks:

First of all, I would like to thank you for asking me to say a few words on Helmut Schmidt’s view on China. Before doing so, however, I have to start with a brief disclaimer. While it is true that I work for the state of Hamburg the following views are exclusively my own.

I think it is quite fitting to briefly think about Schmidt’s narrative on China in this context, for three reasons. First, as is pointed out in the invitation, Helmut Schmidt had a rather clear-cut narrative about China. Not surprisingly, it changed over the course of his life and it was quite controversial in some regards. But it can be clearly defined and discussed, particularly with regard to what Schmidt publicly said and wrote during the last two decades of this life. Secondly, this narrative certainly mattered to Schmidt. Particularly after 2000, he published more on China than about any other country and probably about indeed any other topic. This, thirdly, arguably made him the one public figure with a message on China with the greatest public outreach within Germany.

But to understand how he came to widely disseminate his particular views on China and to be able to discuss its impact today, one has to look at how this narrative developed and how it changed from his time as an active politician to his final three decades as a commentator of current affairs.

So, what I would like to do in the following 12 or so minutes is to first look at how Schmidt thought and acted with regard to China during his time in office. I will then very briefly point out how this narrative shifted after 1982, what Schmidt concentrated on in this narrative and why it was so influential. I will conclude with a few thoughts on what to make of this narrative today.

Schmidt’s view on China, 1958 - 1982

So how did Schmidt view China during his time as an active politician? He later claimed with some pride that he had envisioned China’s rise as early as the 1960s. One has to be careful with such claims. Some of them turn out to be either misleading or difficult to verify. But when it comes to his sincere interest in China and his belief that the country’s weight in international politics would drastically increase in the latter part of the twentieth century, Schmidt was basically right. He did take an interest in a way and at a time that could not be expected of someone with his biography. Already in his first major book from 1961 – “Defense or Retaliation” he included some original thoughts on the People’s Republic. But the questions that he approached here had little to do with globalisation and all the more with security policy. Even so, his political foresight corresponded to his later claims, as he stated (in 1961!): “Long before the end of the new decade – the 1960s – China will have to be regarded as a militarily effective world power. By then at the latest, summit conferences on the fate of the world without China will no longer make sense.” What we find here is indeed his prophecy of China’s rise, a quite remarkable fascination with the development of the country and – perhaps most interestingly – his own original take on China policy.

Why did he take such an interest in China? The answer is the Sino-Soviet split that reached wider public attention in the West in the early 1960s. Unlike most other Social Democrats, Schmidt thought that the relationship between Beijing and Moscow had a direct significance for Germany. In this Schmidt had much in common with some of the more daring foreign policy actors on the political right, most notably Franz Josef Strauß. But unlike the latter, Schmidt did not believe that West Germany could benefit from a Sino-Soviet confrontation and should therefore support Beijing in its anti-Soviet course. Here, Schmidt took a more sober view. Also, in 1961 he wrote: “It is quite questionable whether and from what point on China could become a threat to Soviet policy. It is also quite questionable whether such a development would be helpful to the West, or whether it might not cause an additional threat to peace precisely by inducing Moscow to pursue a policy which it does not originally desire.”

This quote basically wraps up the rationale behind Schmidt’s China policy during his time as Chancellor. He believed that China would clearly matter in the future and that therefore good relations were in the interest of Germany. But above all he wanted to continue Willy Brandt’s Ostpolitik and avoid raising fears in Moscow of an encirclement from East and West. He therefore promoted the nascent economic exchange and development cooperation in non-strategic areas. But whenever the Chinese asked for German arms or made more aggressively anti-Soviet remarks in bilateral talks, Schmidt made it very clear, that Sino-German relations would never come in the way of détente with the USSR.

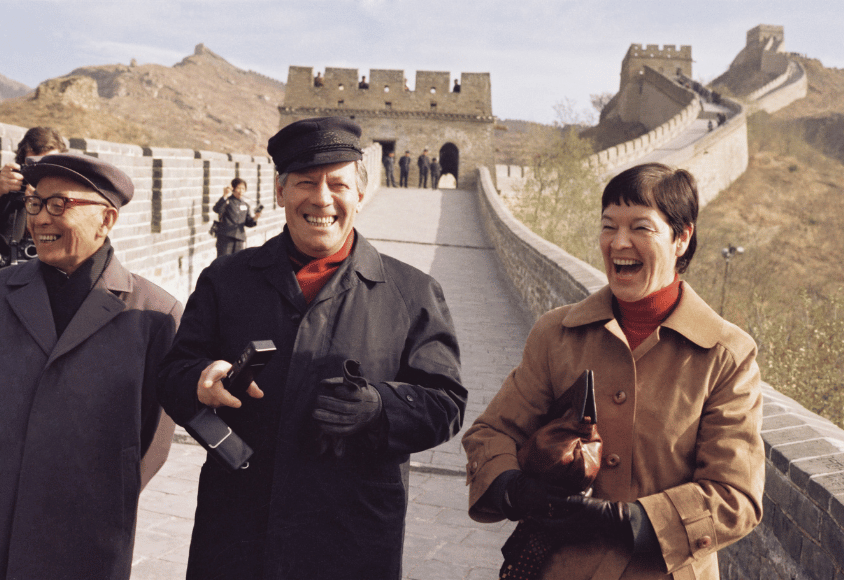

In addition to this generally forthcoming yet slightly reserved attitude towards China, his time in office also shaped his personal view of the PRC because he became the first German head of state to officially visit the country. This trip in 1975 was quite remarkable in a number of ways. Not only did he invite a select group of China experts and top figures from business and trade unions to join him, but also Max Frisch, Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker and Oskar Kokoschka. The latter declined because of his age. Apart from the iconic talk with Mao, Schmidt also had a lengthy conversation with Deng Xiaoping and became the first Western statesman to travel to Xinjiang. Most importantly, he was confirmed in his belief of China’s future importance but he also got a first-hand impression of just how backward the country still was in terms of infrastructure and economy.

Schmidt’s view on China 1982-2015

This last point also serves as the transition to Schmidt’s view on China after leaving office. Because the dramatic economic rise of China, indeed the radical transformation that he witnessed during his later trips to the country clearly shaped his positive impression of the CCP. And it also formed the background to his more and more prolific writing on China policy. To be fair, one has to add that Helmut Schmidt maintained a continuous interest in the country. He travelled there again in 1984 and saw some early signs of growth. And in the first volume of his memoirs – “Men and Powers”, published in 1987 – he devoted almost as much space to China as to the Soviet Union. But the bulk of his China-writing really is from the years after 2000 when China’s GDP and Sino-German trade saw double-digit growth for an unprecedented period of time. It was after 2003 that he came to be associated with the clear-cut narrative mentioned above, which can be summarised in four brief points:

- Since he, Schmidt, had anticipated China’s rise as early as the 1960s, travelled there multiple times and read widely on its history, he understood the country and its culture.

- His reading of Chinese history had taught him that China was the only historic high culture that had survived largely intact and without major changes since its creation 5,000 years ago. China had never acted as an imperialist power and would never do so in the future. Europe had nothing to fear from China except losing its economic predominance to a young and hungry competitor.

- What really drove China and the Chinese leadership was not materialism and definitely not Marxism but what Schmidt believed to have identified as Confucianism. Democracy as a “Western” concept therefore did not fit the Chinese people. Instead, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) guaranteed stability and prosperity and was therefore the right form of government for the culture, proven by the dramatic improvement in living standards from 1978 onwards.

- Germany’s and Europe’s role were to develop mutually beneficial economic relations with China and support the country’s peaceful rise. But they had no political role to play in Asia and they should abstain from interfering with China’s domestic affairs by criticising its human rights record.

Schmidt disseminated this view in numerous talk-shows, interviews and above all in his books, almost all of which became best-sellers. The small volume “Do you understand that, Mr. Schmidt?”, in which he explained, among many other things, why China was his “favourite country”, sold more than 1,2 million copies. Within less than a decade he devoted two entire books just to China’s development. Moreover, he also served as an interlocutor on China for the current Chancellor and his two predecessors. While there are no public written records of these conversations, we have reason to believe that Gerhard Schröder and Angela Merkel sought his advice on China policy at several occasions. And Olaf Scholz did so too before officially visiting the country as the Mayor of Hamburg in late 2011. So, as mentioned above, Schmidt’s China narrative had a very substantial impact in Germany.

What are we to make of Schmidt’s view on China today?

So how shall we evaluate this narrative today and what will last of it? It is of course easy to criticise Schmidt’s narrative in many ways of which I point out only a few. Schmidt’s narrative was unduly simplified and completely ahistorical, which is somewhat ironic because Schmidt claimed that he took history as his guide to understanding China. Particularly with regard to the questions of human rights and democracy, he not only chose to brush off the numerous moments of mainland China’s history when the country could have taken a constitutional turn. Think not only of 1989 but also of 1898, 1911 and 1946. But Schmidt also refused to acknowledge the development of lively civil societies and stable democracies in Taiwan, South Korea and Japan, despite having the same “’Confucian’ legacy” as the PRC.

I think Schmidt actually knew that his China narrative was deeply self-contradictory. The last interview with Giovanni di Lorenzo on China is quite telling in this regard. But he refused to confront these contradictions as this would have forced him to question the entirety of his elegantly simple narrative and also because the CCP-leadership was so nice to him. Who wouldn’t want to be invited to the guest house at Zhongnanhai by the likes of Deng Xiaoping, Hu Jintao or Xi Jinping?

But I think we do not really do Helmut Schmidt justice by only focusing on the obvious – and in some cases highly problematic – flaws in his views on China. Instead we should treat his China narrative as that of a highly complex and multifaceted historic persona. Then we can see that, despite the mentioned flaws, Schmidt also really showed impressive foresight and did get many things right about China. And above all through his actions and his views on China, he also had a considerable and – I think one has to add – positive influence on Sino-German relations and international understanding. On the German side he did much to shape the overall positive image that China had with large parts of the public until the recent past. In doing so he probably also helped countering ever-present tendencies of anti-Asian racism.

As for the Chinese side we can only speculate but I would argue that here, too, he was indeed considered a trusted friend. One has to be careful with these arguments as the CCP has always been very apt at using foreigners for their own propaganda purposes in a rather Machiavellian way. But we also know that communist regimes everywhere are very prone to paranoia and seeing foreign conspiracies everywhere. And here figures like Helmut Schmidt arguably helped to convince the Chinese leadership that they could cooperate at least with parts of the Western establishment in a mutually beneficial way. If one is to look for one key motive that runs through both Helmut Schmidt’s narrative on China and indeed through most of his political life, I would say it is the search for peace and stability. And while this is difficult to measure, I think with regard to Sino-German and Sino-European relations, he succeeded in contributing towards such peaceful and stable exchange.

Conclusion

I want to conclude with my own take on the question if Helmut Schmidt’s China narrative will stand the test of time and continue to have a relevant influence in Germany. My answer is no. Not so much because of his problematic views concerning Confucianism and human rights. But because his China narrative essentially applied to the China and the CCP of Deng Xiaoping, both with regard to the relatively cautious foreign policy and the general trend towards slow domestic liberalisation. And while one can argue about when this China of Deng ended – whether it was 2008 or 2012 or some other date around the end of the nineties - I think it is quite clear that this China has ceased to exist. Schmidt lived long enough to see the rise of Xi Jinping. But partly because of his static view of Chinese history he failed to grasp the fundamental changes going on in Beijing. And as we now have to deal with a China and a world very different from that of fifteen years ago we must treat Schmidt’s narrative – with all its flaws and merits – as history, a thing of the past. For the future, we will need new and very different narratives.