Die komplette Ausgabe des BKHS Magazine „Remaking Globalisation!“ können Sie hier kostenlos herunterladen:

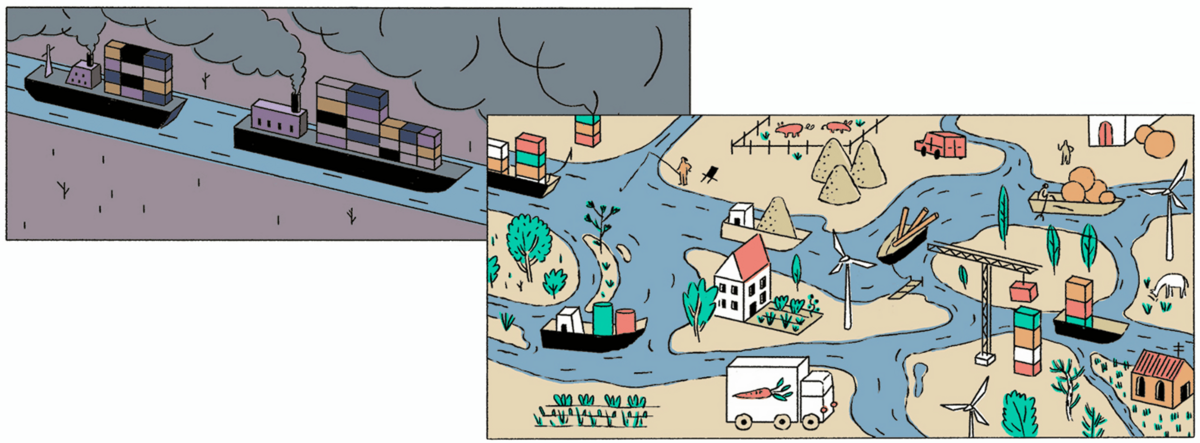

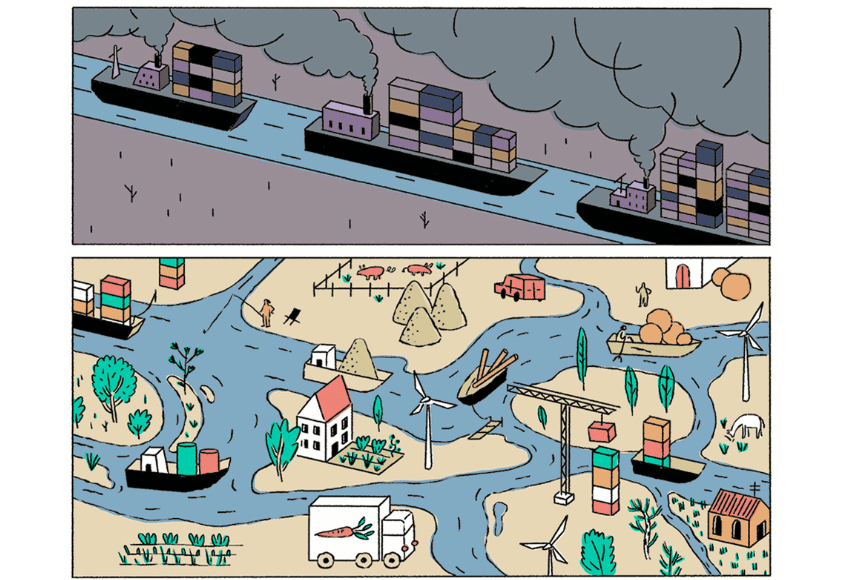

The world is entering a new phase of globalisation. In itself, this is not such a bad thing. Globalisation as we know it desperately needs to be updated to pave the way for a green and just transformation. But unfortunately, this is not the kind of transition the global economy is currently experiencing. A collective understanding of economic security as human security could help to reframe and to redirect globalisation’s trajectory.

Globalisation is of course about far more than just international trade. It refers to a process in which interdependencies between the world’s economy, cultures and populations increase to such an extent that not just goods and services but also social and cultural influences gradually converge around the world. Nevertheless, the core of this dynamic remains the cross-border trade in goods and services set in motion by diplomatic efforts and legal treaties between nation-states. Despite the often-proclaimed demise of nation-states, they remain the main actors in the governing of international trade. As legislative bodies, states control border crossings and determine the conditions and rules of international trade as they negotiate and sign the bilateral and multilateral legal frameworks.

How globalisation challenged nation-states

Although international trade has clearly been promoted by states, the neoliberal demand for a separation of state and economy has dominated international trade policymaking for almost half a century. Until recently, it appeared to be axiomatic amongst policymakers and academics in the Global North that almost any state intervention in the economy would represent interference with the self-regulating “invisible hand” of the market. Accordingly, scholars and practitioners alike expected to see the nation-state retreat from international trade policymaking.

And indeed, for a while it seemed that nonstate actors might take over global trade governance. States increasingly committed to international trade cooperation and even ceded regulatory authority to the multilateral World Trade Organisation (WTO). Over time, the number of WTO member states grew from 128 at the time of its founding in 1994 to 164 today. Members include all major powers, despite their very different political views. Similarly, regional organisations increased in importance as they received rule-making power. The EU, for instance, is also a customs union and single market. All EU member states have delegated their trade policy sovereignty to the European Commission.

Moreover, international organisations such as the WTO opened up their rule-making procedures to trade unions, NGOs and other societal actors. Access to WTO procedures for businesses was also enhanced by the WTO, but this of course started from a much higher level. Additionally, large businesses and their federations increasingly committed to the introduction of new regulations that focused on labour rights and environmental protection.

Nation-states turn back the globalisation tide

As with almost every ideal, the reality is very different. Unfortunately, the WTO has never remotely resembled a multi-level structure with flat hierarchies, as envisaged in its founding documents. One reason might lie in the fact that globalisation as we have known it since the early 1990s has produced winners and losers. Of course, it is far too easy to blame the WTO alone for the short-comings of global trade governance. A major problem has always been that member states rarely search for common ground. Instead, they are driven mainly by their own national interests that they balance up against each other when shaping international trade regulations. This can be illustrated by the fact that the WTO’s member states have not been able to conclude any major agreement since the organisation’s foundation in the mid 1990s. Several issues, even minor ones, have dragged on for years. A major controversy, for example, relates to agricultural subsidies between the Global South and the Global North.

Even though almost every country was interested in joining the WTO, each state started with a different set of resources. Some states were rich in money and big business, others had plenty of natural resources at their disposal, while still others had an abundance of cheap labour. As a consequence, WTO member states have diverged in their financial ability to engage in WTO consul-tations to advocate and advertise for those regulations most beneficial for themselves. Moreover, some WTO member state economies have been at a disadvantage when competing with their already industrialised and digitised counterparts. From the outset, the economies of the richer states were better of. Several emerging markets have been able to catch up, yet large parts of their societies have still been left out in the cold, disadvantaged by globalisation. As calls for institutional reforms of the WTO go unheard, these countries unsurprisingly have lost trust in the international rules-based system.

These challenges of global inequalities, however, did not ignite the current discussion about “the death of globalisation”. This debate only took hold when the Global North began to experience the downside of globalisation first hand. Today, the developed world fears the consequences of globalisation – and the economic interdependence it brought about. Perhaps the most significant buzzword we have heard in this debate over the past few years is “weaponised interdependence” (Farrell & Newman 2019). The claim is that states such as China and Russia are exploiting the “West’s” economic dependence on their resources to press for strategic and security political gains.

This revival of geoeconomic tactics – the use of economic means to achieve security-related goals – has been fuelled by successive years of events that have rocked the global order. The economic repercussions of the 2008 financial crisis severely challenged the US and the EU. Then, in 2016, Brexit and the election of Donald Trump shook both sides of the Atlantic. At least some voters saw globalisation, along with technological change and deindustrialisation, as a cause of their economic stagnation or even social decline (Rodrik 2021). Distrust in democracy, economic nationalism and protectionism increasingly gained traction.

As globalisation advanced, many individuals clearly felt unheard. While businesses enjoy easy, and most importantly, influential lobbying access, representatives of the public receive less attention and struggle for impact. This is particularly problematic because it means issues that have direct consequences for individuals – such as environmental protection, labour and human rights regulations – occupy a much lower position on the agenda.

Trump’s trade war against China and allies such as the EU, coupled with interruptions of global supply chains that lasted for years due to the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing insecurities in production driven by climate change, Russia’s war against Ukraine and the subsequent energy crisis have caused globalisation to break down even further. As more states “weaponise interdependencies”, reducing economic linkages becomes desirable as a way to reduce political vulnerabilities. The upshot is that state interventions in economic and trade policies have almost become the new normal.

Globalisation as we know it not only neglects the interests of the Global South. It also impacts on the needs of the planet and of many people in the Global North. Moreover, the current transformation of globalisation is neither green, nor just. Instead, globalisation seems to be on a path to fragmentation, frequently along nationalist and ideological lines. It is no longer the case that the opportunities globalisation can offer guide today’s policy decisions. Rather, its potential risks are what count. Economic interdependencies – once celebrated as a tool to make wars less likely – are being weaponised in the pursuit of security policy objectives.

Introducing human security to international trade policymaking

Today, governments on both sides of the Atlantic are questioning the “laissez-faire” approach to globalisation they have propagated for several decades. Many believe we are seeing the first shift to the economic paradigm in the Global North since the 1980s. But instigating change to a process as complex as globalisation is difficult. Russia is instructive when considering the difficulties of disentangling economies: for almost two years, G7 countries have tried to isolate Russia from the world economy by imposing massive sanctions, but have had only minor success.

Change is particularly difficult due to the current great power rivalry. Security concerns often trump economic considerations. But the future nature of the security-trade-nexus is still up for debate. It will be shaped not just by the different interests of nation-states and their relationships with one another, but also by the growing climate crisis. A progressive understanding of economic security should include a just and green transformation of globalisation. States will remain central to the adoption of such strategies, because national security is still a policy area in which states protect their sovereignty against the involvement of non state actors.

To date, there has been a lack of a common understanding of de-risking and economic security amongst decision-makers. “De-risking” is a new concept for states. Since it was introduced to the world by EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen in March 2023, representatives of govern-ments, think tanks and lobby firms have all been eager to define the new strategic imperative. For its part, “economic security” as a concept has a much longer pedigree, at least in academia. But the economic security strategies of various countries have only recently risen to prominence. Japan, as an early mover, introduced it to the G7, which in turn agreed upon the goal of economic security at its 2023 Hiroshima Summit. However, the members’ national approaches (still) differ in their priorities and specific policy measures.

Strength in numbers: the future of human security

In my view, the global trade order lacks a collective economic understanding of “human security”. Human security focuses on individuals as the primary object of security and therefore includes “issues such as poverty, underdevelopment, hunger and other assaults on human integrity and potential” in its definition (Buzan & Hansen 2009: 36). If states approached economic security through a human security lens, they would take the lives and risks of individual people into account when making policies. They would reconsider the different sectors in society and would seek to completely reframe economic and security policies.

Japan and the EU have already introduced economic security strategies. At the national level, they focus on security, the economy and technological challenges. Internationally, they consider supply chain risks. However, analysis at the level of the individual play only a minor, subordinate role. Positively, the first steps taken by the US towards a definition of economic security do include elements that potentially point more in the direction of human security. The aim of the Biden administration is to “build capacity, to build resilience, to build inclusiveness, at home and with partners abroad” (Sullivan 2023). Nevertheless, the US position often puts America first, promoting economic nationalism and forgetting about the humans involved throughout supply chains.

If a larger group of states were to jointly reinterpret economic security as human security, they could reframe and redirect the current path of globalisation. Understanding globalisation and economic security less as a trade-of would allow for globalisation to be remade in a way that ensures economic security not in spite, but because of a green and just transformation.

References:

- Buzan, Barry & Lene Hansen (2009): The evolution of International Security Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Farrell, Henry & Abraham Newman (2019): Weaponised interdependence: how global economic networks shape state coercion. International Security, 44(1), 42-79.

- Rodrik, Dani (2021): Why does globalization fuel populism? Economics, culture, and the rise of right-wing populism. Annual Review of Economics, 13, 133-170.

- Sullivan, Jake (2023): Remarks by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan on renewing American economic leadership at the Brookings Institution. The White House, 27 April 2023, www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2023/04/27/remarks-by-national-security-advisor-jake-sullivan-on-renewing-american-economic-leadership-at-the-brookings-institution/.